In my experience, and I know other people’s experience, of interpreting literature as a queer person, sometimes it’s important to try to put yourself into these texts that aren’t for you.

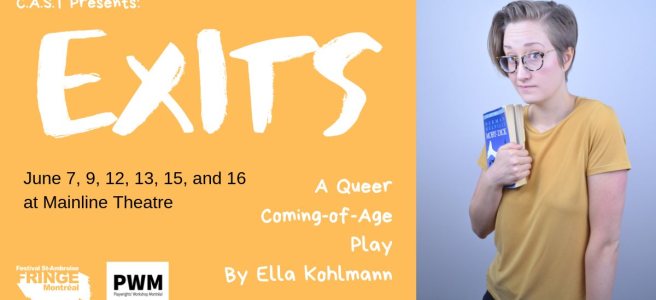

A young girl runs away from home with nothing but a copy of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and the ghost of her eleven-year-old self. That’s an abridged summary of Exits, being produced at the St-Ambroise Montreal Fringe Festival in June. I sat down with playwright and actor Ella Kohlmann and director Madie Jolliffe to discuss this coming-of-age play.

Answers have been edited for clarity.

Can each of you describe in one sentence what Exits is about?

EK: I mean, the one that I always use is, “It’s a queer coming of age story about graffiti, Moby Dick, and running away.”

MJ: It’s about dealing with all the big questions while also having to deal with not being straight while growing up.

Ella, you not only wrote the play but you also play the main character. What was it like making the jump from playwright to actor?

EK: Weird, but fun. I think the main thing is I had to get to a point with the script where I felt comfortable enough with the text that I could just go, “All right, it’s done, here we go,” and put my actor hat on. I also just feel really supported by the crew I’m working with, and Madie’s a really great director, so I feel like I’m in a safe and comfortable place to let it be something that I’m no longer nit-picking at and to just have this role instead of such a control-y one.

This play is being produced thanks to the Concordia Association of Students in Theatre. I’m curious to know, what was their reaction to this play when they accepted it? I guess, what was their reaction and what was your reaction as well?

MJ: Their reaction was just “yes” basically. They just said, “Yeah, you get to do it.” But talking to members of CAST they said they were really excited. I was super thankful because I’m graduating from the department, and because I’m not a performer, I didn’t get a big, final production. This feels like a Concordia thing because everyone we’re working with, even our minor, we’re working with because of Concordia. It feels to me like we’re being recognized before I leave.

EK: It felt like a really good opportunity to do something outside of school that still feels supported by school, like a kind of safety net. Money support, of course, is nice, but also to feel like there’s this community here that we feel we can go back to.

Madie, what drew you to this piece as a director?

MJ: Lots of things. Number one was just, Ella, we’ve been working together for a couple of years now. How fun is that to say?

EK: Time isn’t real.

Laughter.

MJ: Ella and I work well together and I’ve gotten to see a lot of Ella’s writing come to life in different ways in different classes. Being in the Young Creators Unit [at Playwrights Workshop Montréal] together, I’ve gotten hints of the show. I think Ella’s one of the best writers I know, so when she was like, “Hey do you want to direct my play for something?”

EK: This was before Fringe, I was just like, “I want Madie to direct!”

MJ: It felt really nice that I was the one that Ella wanted. I’ve been directing a lot of shows recently that have been the writer performing in it and being in the rehearsal room, so I feel like I’ve had practice negotiating that relationship. This is a pretty big piece, but I felt comfy in doing it with Ella because of how we’ve worked together before. But it was also the show itself. As a queer person, it took so long to sort out that part of me. I’ve never even seen a show about a queer young person before. So just that aspect alone, I’m like, “This is a show that has to be onstage.” But there was also a lot of space for me to interpret it and put my own artistic style on it.

Laughter.

EK: Our lighting and sound designer, Amy [White], has been really amazing. It’s been gift after gift after gift that I’m getting from her, because I’ll write a stage direction and be like “This is the vibe or the feeling,” or I write something poetic that I want from it, and then she’ll come in and be like, “It’s underwater,” or “It’s this, that, we’re doing these things with lights!” And it’s like, wow, you understand! I’m not very prescriptive; I like to keep things open to interpretation.

This was part of Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal’s Queer Reading Series back in January/February—yours was January 31st—how instrumental was PWM in helping develop this play?

EK: So instrumental. I technically started writing this piece when I was seventeen, when I was in grade twelve. It sat on my computer for a little while after that. I came back to it because I joined the Young Creators Unit two years ago, and I was like, “I have this rough thing that is not quite a play yet that I would love to go back to and turn into a play.” Jesse Stong from Playwrights’ Workshop and the Young Creators Unit dramaturged it with me and was super instrumental in me figuring out what I wanted out of this piece. Also being able to put it up in the Reading Series was so useful both for me in my process of writing and seeing it put on its feet. I’m acting in it now, but I didn’t act in it in the Reading Series, so that is another reason why the transition was easy for me, because I got to see it realized by someone else.

MJ: I went to the Reading Series. I hadn’t touched the play yet—I had read it and done my own work on it, but I hadn’t really talked to Sarah [Segal-Lazar] who directed it, so getting to see it, a lot of beautiful little details came out of the reading that were surprising, like the way they did the spray paint. It was different from what Ella and I were envisioning, but it was super beautiful, so we’re stealing that. Laughs.

What was it like going back to a play that you started when you were seventeen? Do you feel like you’re playing your seventeen-year-old self? Or has it evolved passed that?

EK: I mean, yes. This is the play that I taught myself how to write plays by writing, because it’s the first play I had ever written. It’s not literally me, obviously: I never ran away from home, I never met a girl doing graffiti in a back alleyway, I never read Moby Dick when I was seventeen, but there’s a lot of myself in the character. In the play, the seventeen-year-old character is having conversations with her eleven-year-old self, and in working on this play and performing it now it feels like I at twenty-one am having a conversation with my seventeen-year-old self. I think a lot of the reasons I came back to it was because I wanted to write something for me back then and for people like me. If you feel like you’re not seeing yourself onstage or in art it can feel really isolating to not know where you fit inside of stories. Another part of what I’m exploring with this piece is, “What does it mean to feel really connected to works of art—in this case it’s Moby Dick—but that isn’t necessarily written for you?” I don’t think Herman Melville was like, “Ah yes, a seventeen-year-old lesbian in 2019 is going to be really invested in my book about whaling, but she is, and she’s finding ways to see herself in it and interpret her own life in it, and I think there’s something really vital about that. In my experience, and I know other people’s experience, of interpreting literature as a queer person, sometimes it’s important to try to put yourself into these texts that aren’t for you. But then at the same time it sucks to have to do that work, when you aren’t seeing these stories.

My last question is, how important was it for you to put together a group of queer artists to work on this show?

EK: I think part of it is feeling like I’m working with people who understand the things that I’m exploring. But also in a very straight-white-male-dominated industry, it’s always good to make sure that you’re giving space and opportunity to diverse voices. One of the most exciting parts of working on this piece is working with Oli [Hausknost], who is our fourteen-year-old who is playing Young Rachel. It would feel really hypocritical to tell this story and not have the people who are telling it be part of this community.

MJ: It was also lucky. I feel like we’re so plugged into a queer network, too, so we were like, “Who do we want to work with on this? Oh, they just happen to be gay!” Finding Oli was such a precious thing because sometimes working with minors, you have to consider so many things, like what is someone’s exposure to gayness in the world? What is that for them? So that was really special, to find someone who could engage with the content as a young person, because they’re just so much more self-aware than I was at that age, so it was really refreshing.

EK: The kids are alright.

Catch Exits at the St-Ambroise Montreal Fringe Festival June 7-16 at Mainline Theatre. Buy tickets here and check out the Facebook event here.

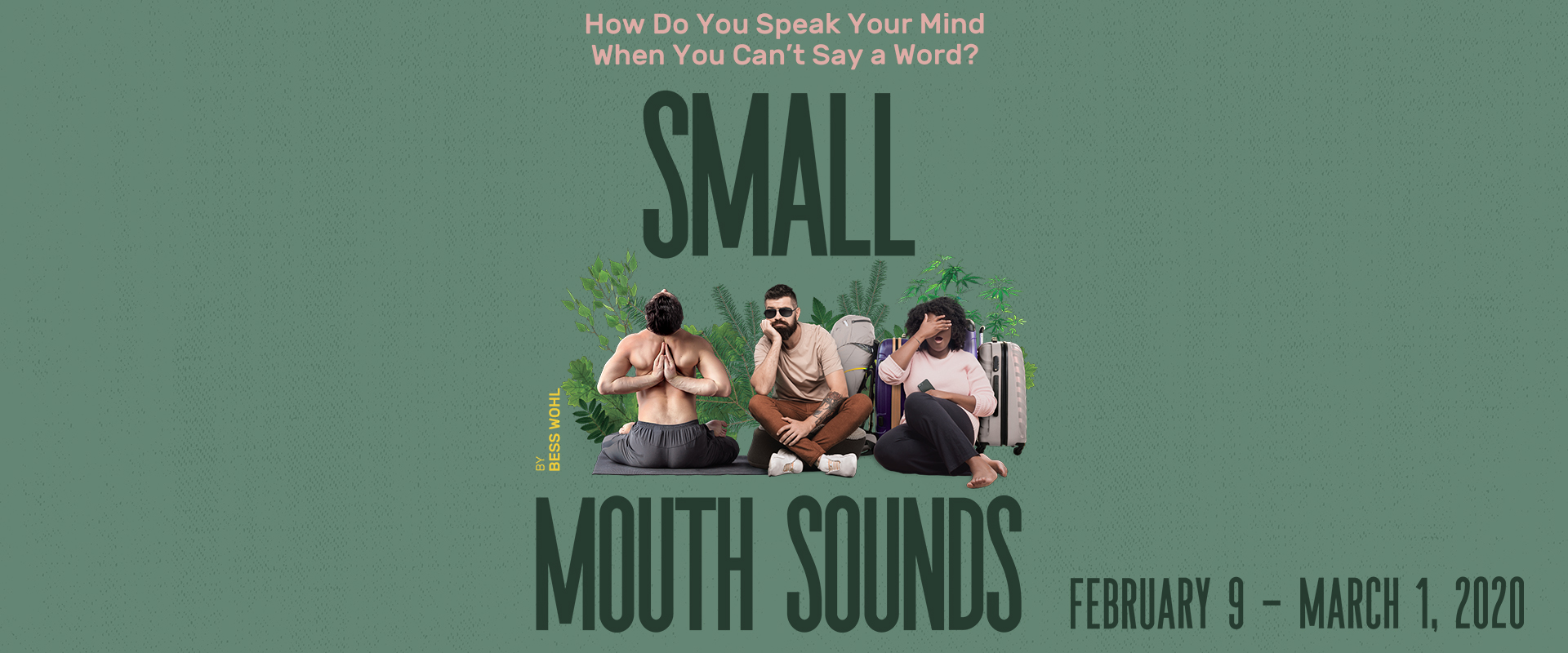

Originally directed by a personal favourite, Rachel Chavkin, Small Mouth Sounds by Bess Wohl treks its way to the Segal Centre in a production directed by Caitlin Murphy. In this one act, 90-minute play, six individuals sign up for a five day silent retreat led by the mysterious “Teacher.” Whether running away from illness, loss, or a series of tragedies, all are in search of enlightenment, to varying degrees of success. It might be obvious to say that in this play, which includes little dialogue, it’s what remains unsaid that counts

Originally directed by a personal favourite, Rachel Chavkin, Small Mouth Sounds by Bess Wohl treks its way to the Segal Centre in a production directed by Caitlin Murphy. In this one act, 90-minute play, six individuals sign up for a five day silent retreat led by the mysterious “Teacher.” Whether running away from illness, loss, or a series of tragedies, all are in search of enlightenment, to varying degrees of success. It might be obvious to say that in this play, which includes little dialogue, it’s what remains unsaid that counts The One

The One